Unit 3 Breakdown

You are on Lesson 1 of 4

- Unit 3.1 | Understanding circular motion and centripetal forces (Current Lesson)

- Unit 3.2 | Solving circular motion problems using FBDs

- Unit 3.3 | The gravitational force

- Unit 3.4 | Combining circular motion and gravitation (satellites, orbits, and more)

In this lesson:

- You will learn about centripetal forces and acceleration

- The similarities and difference between linear and centripetal foces

- Equations for circular motion

- Common situations involving centripetal forces

Introduction

So far you’ve covered forces such as weight, friction, and normal force. These are all linear forces, because they accelerate objects along a straight, linear, path.

Circular forces, on the other hand, move objects in circular paths. Yet, you’ll learn that these circular forces are much like linear forces…with a caveat.

How Can a Force Be Circular?

In Unit 1 Kinematics, we defined acceleration as a change in speed or direction.

Imagine a car going around a racetrack at a constant speed of 60 mph. In this scenario, the driver turns the steering wheel to change the direction of the car.

The continuous change of direction, as the car travels around the tack, is why we say the car is accelerating. And we call this type of acceleration “centripetal acceleration.”

So despite traveling at constant speed, the change in direction direction of the car causes an centripetal acceleration.

Relation to Linear Forces

Let’s connect this to linear forces.

Recall Newton’s 2nd law: a net force acting on a mass will cause an acceleration [katex] F_{net} = ma [/katex].

In circular motion, it is the net “centripetal” force that causes a centripetal acceleration.

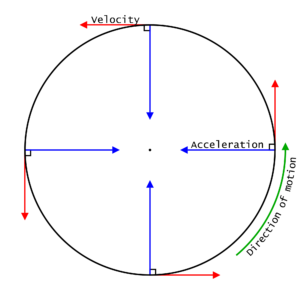

Furthermore, both centripetal force and acceleration point INTO the circle at any given point. We’ll discuss why in a moment.

So just like in linear forces let’s use Newton’s 2nd law again, but this time use subscripts to indicate a centripetal acceleration:

[katex] F_{net} = ma_c [/katex]

Note – [katex] a_c [/katex] means centripetal acceleration.

Inwards!

So why do centripetal forces (and acceleration) point into the circle?

Well it turns out that objects don’t naturally want to move in a circle.

Remember Newton’s 1st law? An object in motion will want to resist any changes in its motion.

This means that an object is fine traveling in a straight line without resistance. However, the moment something tries to “bend” the path, the object will try to resist that change in motion.

Thus we need a inwards force, to “force” the object to bend into a circular path. We call this the “centripetal force.”

Without the centripetal force an object will just continue to move in a straight line.

Uniform Circular Motion

Quick note: The title of unit is “Uniform circular motion.”

The word “uniform” refers to the object’s constant speed as it moves in a circular path.

If the speed were to change, the object would also experience a tangential acceleration (in addition to its centripetal acceleration).

Recap

To summarize everything so far:

- Centripetal forces and centripetal accelerations are similar to linear forces and linear accelerations. The only difference is centripetal forces and accelerations point into the circular path.

- Without a centripetal force pointing into the circular path, the object would just move in a straight path (according to Newton’s 1st law).

- Uniform circular motion typically involves a “uniform” (aka constant) speed. The centripetal acceleration comes from a change in the direction of the object.

- If the object were to speed up or slow down as it moved in a circle then that would cause a linear (tangential) acceleration.

Centripetal forces are normal linear forces

With your understanding of why centripetal forces point inwards, let’s learn what forces are actually pointing inwards.

The first point to note: The “centripetal force” isn’t a separate force but a term for the net force directed towards the center of the circle. To understand this better, take a look at the example below.

A car drives around a circular, ice-covered track. What happens to the car if it goes too fast?

It would skid of the track! This indicates the force of friction, between the tires and the road, are responsible for “pulling us in.” Therefore, in this example the force of friction is the centripetal force, and it points toward the center of the circular path.

To recap: The “centripetal force” is sort of a placeholder for the actual inwards force.

Another example: Imagine spinning a yo-yo toy in a vertical circle. What is the centripetal force that moves the yo-yo in a circle?

If you said the force of tension, you would be right! The tension in string of the yo-yo pulls it into a circular path.

Direction

As you just learned, centripetal acceleration (and centripetal force), ALWAYS points into the circular path.

But what direction does velocity point at any given point?

Velocity is always acts tangent to the circular path. In other words the velocity vector just touches the circle at one point.

For example, imagine Figure 1 is someone spinning a yo-yo in a vertical circle. When the yo-yo reach the bottom most point, the yo-yo string snaps. There’s no force of tension to create a circular force. Which direction would the yo-yo go flying the instant the string breaks? Up, down, left, right, or somewhere in between?

Answer: The yo-yo will fly straight to the right, following its tangential velocity at that moment. According to Newton’s 1st law, in the absence of forces, the object will continue moving in its original direction, which is tangential in this case.

Conceptual Practice

Answer these four conceptual question. Thoroughly understand the explanations before moving on.

Which of the following do not affect the maximum speed that a car can drive in a circle? Choose both correct answers.

The acceleration due to gravity.

The coefficient of kinetic friction between the road and the tires.

The coefficient of static friction between the road and the tires.

The mass of the car.

The radius of the circle.

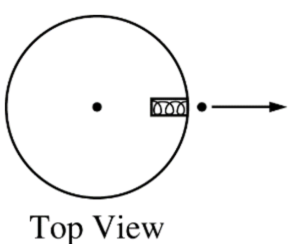

A compressed spring mounted on a disk can project a small ball. When the disk is not rotating, as shown in the top view above, the ball moves radially outward. The disk then rotates in a counterclockwise direction as seen from above, and the ball is projected outward at the instant the disk is in the position shown above. Which of the following best shows the subsequent path of the ball relative to the ground?

A compressed spring mounted on a disk can project a small ball. When the disk is not rotating, as shown in the top view above, the ball moves radially outward. The disk then rotates in a counterclockwise direction as seen from above, and the ball is projected outward at the instant the disk is in the position shown above. Which of the following best shows the subsequent path of the ball relative to the ground?There is not enough force directed north to keep the package from sliding.

There is not enough force tangential to the car’s path to keep the package from sliding

There is not enough force directed toward the center of the circle to keep the package from sliding

The force is directed away from the center of the circle.

None of the above.

Planetary Orbits – Quick Note

Planets move around in elliptical orbits, not circular orbits. Therefore, we must use Keplr’s laws to analyze planetary motion. Although we do NOT cover Keplr’s laws in this course, there is a clever work-around.

In many Physics courses we approximate the orbits of planets to be circular. Hence, we can apply the principles of circular motion to planets.

So if you see questions involving planets, you can use equations from circular motion!

Equations for circular motion

Since centripetal forces are still just regular forces, the only new formula you need to know for centripetal acceleration:

[katex] a_c = \frac{v^2}{r} [/katex]

In this formula, [katex] v [/katex] is the tangential velocity of the object, and [katex] r [/katex] is the radius of the circular path.

Now let’s use Newton’s 2nd law to derive an equation for centripetal force:

- Start with Newton’s second law: [katex] F_{net} = ma [/katex]

- Replace linear acceleration with centripetal acceleration: [katex] F_{net} = ma_c [/katex]

- Replace ac with the already made equation for centripetal acceleration: [katex] F_{net} = \frac{mv^2}{r} [/katex]

Remember, when it comes time to solve a problem it is your job to determine [katex] F_{net} [/katex] and plug in relevant values.

Lesson 3.2 Preview

In the next lesson we will use FBDs to start solving real word circular motion problems.

This typically involves problems with rollercoaster, cars, spinning objects, and much more.